When a couple, married or not, live in a property which is legally owned by one or both of them, questions can arise as to what their respective beneficial interests are. A simple example will make this clear.

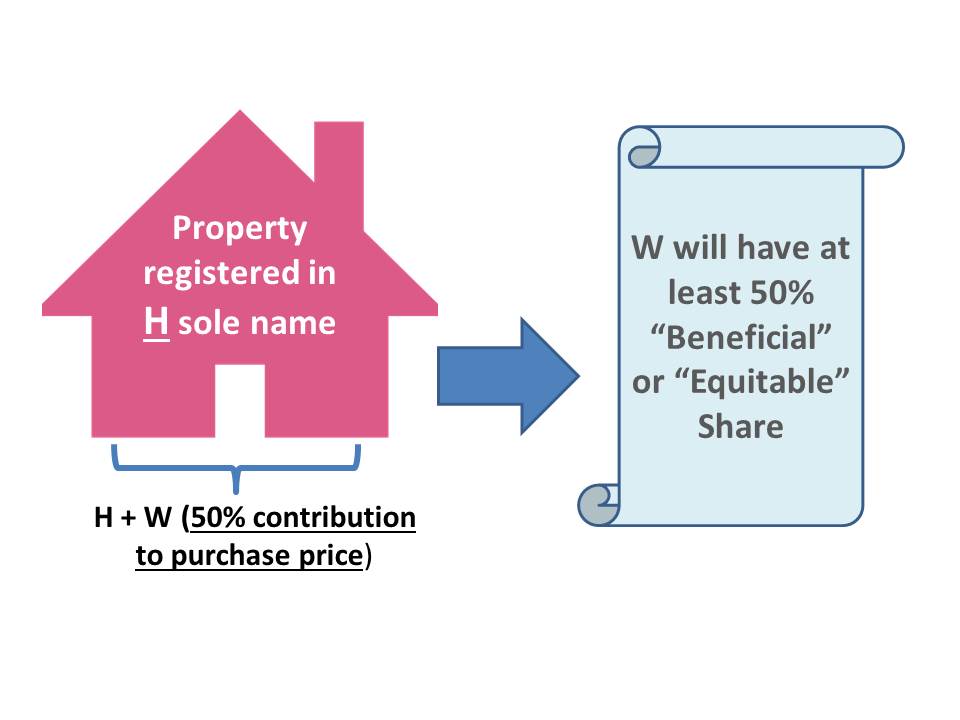

H and W live in their matrimonial home, which is registered in H sole name. But W contributed fifty percent of the purchase price. The law recognises W’s contribution and she will have at least a fifty percent “beneficial” or “equitable” share in the property. In effect, H holds the property on trust for the two of them.

The mechanism by which this conclusion is reached is quite complicated and depends on the application of different types of trusts.

The idea is to discern what the couple’s intentions were when the property was acquired. The fact is that people do not really address this issue at the relevant time except in the most general way. The result is that if an issue arises as to the ownership of the property – because, for instance, one of the parties dies and a third party claims entitlement to his or her estate – the court has to fill the gap and decide what the parties’ respective intentions were when the property was acquired.

The solution is provided by the application of what are called resulting and constructive trusts.

Briefly, in the case of a resulting trust the law presumes what the parties’ intentions were when they acquired the property, by looking at the surrounding circumstances, in particular, their respective contributions to the purchase price. This is referred to as the presumption of a resulting trust. It does not operate if the parties’ intentions were, as a matter of fact, and law, made expressly clear at the time, but this is a fairly unusual scenario.

The point is that there is a presumption against gifts. This if A pays a million dollars for a property and gets it registered in the name of B, there is a presumption that B holds the property on trust for A, unless there is evidence to indicate that a gift was intended; that evidence can be used to rebut the presumption. It is different, though, if B is A’s wife, or child (even adult child). Then there is a countervailing presumption, the presumption of advancement, which can, again, be rebutted by evidence that no gift to the wife or child was intended.

An example might make this clear. In a Court of Appeal decision a few years ago, Lau Siew Kim v Yeo Guan Thye Terence, an engaged couple purchased, as joint tenants, two properties, one the matrimonial home, and the other an investment property. Both parties contributed to the purchases, but not equally. When the husband died, the wife remained the sale registered owner of the properties because of the right of survivorship (explained in Part One). But the husband’s sons from his first marriage claimed that she held both properties on trust for his estate, on a resulting trust. The Court of Appeal disagreed. Although the presumption of a resulting trust was raised by the fact of unequal contributions to the purchase price, it was rebutted by the presumption of advancement in favour of the then fiancee. (The court’s decision was based, inter alia, on its consideration of the nature and quality of the relationship.) They were both legal and beneficial – equitable – joint tenants and the wife was now the sole owner.

Common intention constructive trusts are quite different. With a resulting trust, unless the plaintiff can rely on the presumption of advancement, he – or more probably she – is likely to be limited to a proportionate share of the property based on her contribution to the purchase price.

With the common intention constructive trust, on the other hand, the court examines the dealings and conduct of the parties at the time of the acquisition in order to discern what their common intention was; the party who contributed less may well have acted to his or her detriment on the faith of such a common intention, justifying a bigger “slice of the pie”.

This is an area of law where the Singapore courts have diverged significantly from their English counterparts. In England, the default approach – where the couple have bought a home together as joint tenants – is to presume that their beneficial interests are equal unless there are factors indicating an agreement to share on a different basis, applying constructive trust principles. There is an increasing tendency towards “fairness” – doing justice between the parties irrespective of their financial contributions. The resulting trust, and in particular the presumption of advancement, are thought to be out of step with contemporary social mores.

In Singapore, by contrast, the resulting trust is the default mechanism for resolving disputes concerning matrimonial or quasi matrimonial property. Only in special circumstances will the courts resort to the common intent – constructive trust.

In short, there is a considerable degree of uncertainty regarding the respective interests of cohabiting couples – whether married or not – in residential property that they acquire jointly. It makes sense for such couples, when contemplating the purchase of a property, to seek legal advice as to how they want the property to be divided in the event of same unforeseen event.