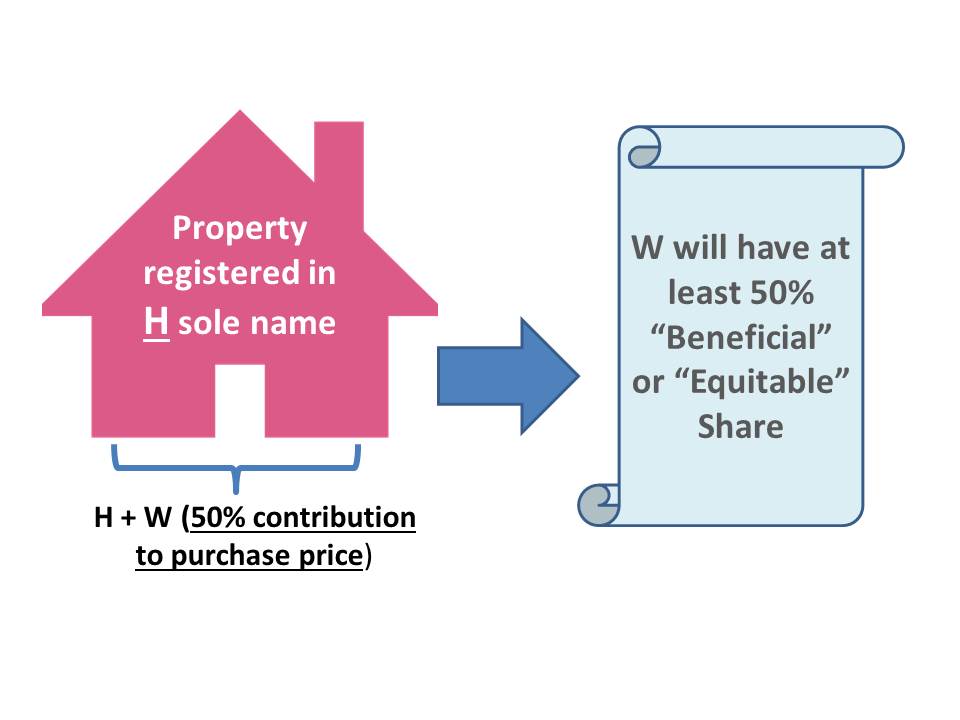

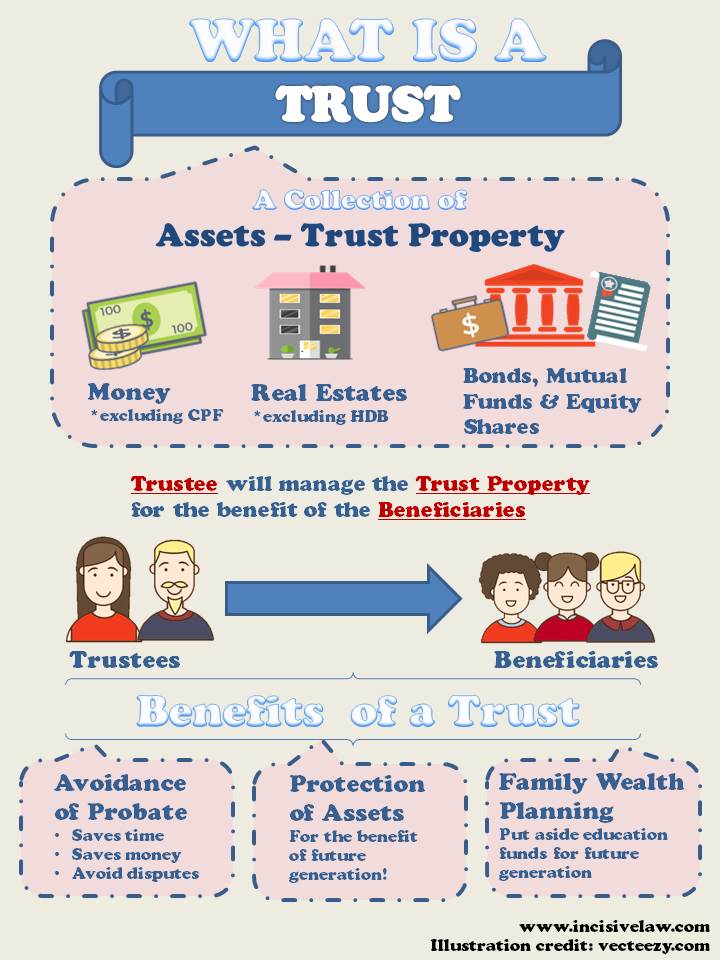

A trust is created upon the transfer of assets (“the trust property”) by the settlor to a person (“the trustee”) on the basis that the trustee shall hold the assets for the benefit of other people (“the beneficiaries”).

The trustee is now the legal owner of the assets and has a fiduciary obligation to act in the best interests of the beneficiaries.

Vector Design by www.vecteezy.com

The settlor can settle most types of property into the trust, although there are exceptions such as HDB flats and CPF funds, amongst others. The trustee has management control of the trust property but it is the beneficiaries who are entitled to use and enjoy it.

There are two forms a trust can take. A fixed trust is one where the settlor has already allocated the proportions of benefits each beneficiary gets, with no discretion available to the trustee, while a discretionary trust is one where the trustee is granted the power to exercise discretion with respect to which beneficiaries benefit under the trust and the amount they get.

The benefits of a trust arrangement over a will are listed below.

Avoidance of Probate

Probate is the name given to the court document which certifies the authenticity and validity of your will and confirms the powers and authority of your appointed executors to administer your estate. It is compulsory to produce this document to be able to sell and transfer the deceased’s assets. This can be burdensome and inconvenient as many assets will be frozen pending the completion of the process.

However, in a trust arrangement, in the event of the settlor’s death, the assets settled into a trust will not form part of the deceased’s estate. Hence probate is not required on these assets and disputes over the assets can be avoided.

Protection of Assets

A trust is a useful tool to protect your assets and preserve them for the use and benefit of future generations. As the ownership of the trust assets is with the trustee and not with the settlor, a trust structure can protect a settlor’s assets from the grasp of the settlor’s creditors. However, if you are made bankrupt within 5 years after transferring assets to a trust, your creditors will be easily able to unwind the trust and claim the assets toward satisfaction of the sums due to them.

Family wealth planning

If there is a need to provide for financially irresponsible family members, a trust may be particularly useful. The beneficiary’s interest can be made terminable on the occurrence of a certain event, such as the beneficiary’s insolvency, at the trustee’s discretion.

Whether or not a trust or a will is more suitable for you depends on your individual concerns. We will be happy to sit down and discuss your options with you. Do drop us a message here.